Mala daydreaming

I’ve never been one to look too far into the future or dwell on the past. I’ve always seen that as a kind of superpower. I don’t get crushed when things don’t unfold the way I imagined. I’ve lived by the code that nothing is promised, and that’s always made sense to me.

Generally, I’m rooted in the here and now. I don’t get ahead of myself—it's my thing!

A perfect example of this happened yesterday.

A bit of context for this story-within-a-story: I recently started a new band with my brother and a mate. We’ve been at it for the past four months—writing, rehearsing, doing the whole blah-blah-band-startup grind. We’d written four songs we were happy with, but we didn’t have a bassist. Enter: Join My Band (big up). I found a bassist, and everything was great—almost too great, if I’m honest. The guy picked up the songs in a single practice, but I was suspicious. Musically, he was on another level to the three of us—and Tom (guitarist) and my brother (drummer) are both genuinely talented.

I remember thinking at the time, this guy should be in a pro band. Something felt off. I’ve been around long enough to spot a flake a mile away, and I knew exactly how it was going to play out—he wasn’t going to stick around. Sure enough, after three practices he said he couldn’t commit because of work. I can smell horseshit from miles away. If you really want to do something, you’ll do it. No excuses. Basically, the point of that little story is that both my brother and Tom seemed quite deflated and disappointed about this guy leaving the band. I saw it coming and it didn’t affect me if anything, it strengthened my resolve to make this band at least play some shows. Stubborness.

Back to my original story… Don’t get me wrong, I’m a serial daydreamer. I’m often off in another world, with storylines constantly playing out in my head. I pick them up and drop them all the time—some of them have been running for years. I’ve since learned that this is common, especially among neurodiverse folks. It’s called maladaptive daydreaming. I’ve used it as a coping mechanism for as long as I can remember. Before writing this, there was only one person I’d ever spoken to about it. Much like my autistic tendencies, I kept it hidden for years because I thought it was strange and that people would judge me for it. Honestly, I didn’t even know it had a name until I finally talked to someone about it.

When I think about maladaptive daydreaming—and when it first shifted from something harmless into something that quietly shaped the way I lived—I always find myself tracing the thread back to childhood. I was a kid who lived almost entirely in my imagination. Not in a quirky, once-in-a-while way, but deeply. Daily. I’d create stories and entire universes for my toys, building characters, conflicts, and endings that only I ever knew about. My imagination wasn’t something I switched on; it was simply the world I spent most of my time in. It felt safe there. Predictable. Mine.

Even though I have a younger brother, I spent a lot of time alone. We’d often play football together, but it usually ended with fisticuffs and tears—when I won, obviously. The truth is, I preferred my own company. I liked the control, the quiet, the ability to disappear without explanation. While other kids seemed to live in the real world with ease, I drifted between the outer world and the inner one in my head.

Looking back now, it’s obvious this was more than just a child’s overactive imagination. It was a coping mechanism, a sanctuary, a way to navigate emotions I didn’t yet have the language for. I didn’t know it at the time, but this habit—would eventually grow legs of its own. What began as innocent play slowly became an escape, only returning to reality when necessary. As an adult, naming it “maladaptive daydreaming” gave it shape. A word. A frame. Suddenly I could look at it with some understanding instead of the shame or confusion I’d carried for years. But its roots were always there, tangled up in childhood days spent wandering worlds no one else could see.

These days, I go through phases of what I’ve decided to call “mala daydreaming” (my cool new rebrand for it). When it’s bad, it becomes almost all-consuming. It always flares up when I’m stressed or anxious, like my brain’s built-in escape hatch pulling me away from whatever’s happening around me. It takes time to centre myself and return to the present, but I’ve started to learn techniques that stop me from living entirely in my head. The biggest shift is awareness. I actually notice when it’s happening now. I compare it to doomscrolling on my phone: I get sucked in without realising it, disappear into this trance for ten, twenty, thirty minutes… and then suddenly you snap back, wondering where the hell the time went. Mala daydreaming feels exactly like that. It’s a mental rabbit hole I slip into without meaning to, and only later do I realise I’ve vanished from the room altogether. The difference now is that I know the signs—when my thoughts start drifting, when the storylines start forming, when reality starts to fade. I can pull myself back before it swallows me whole. It’s still a work in progress I’m learning to live here instead.

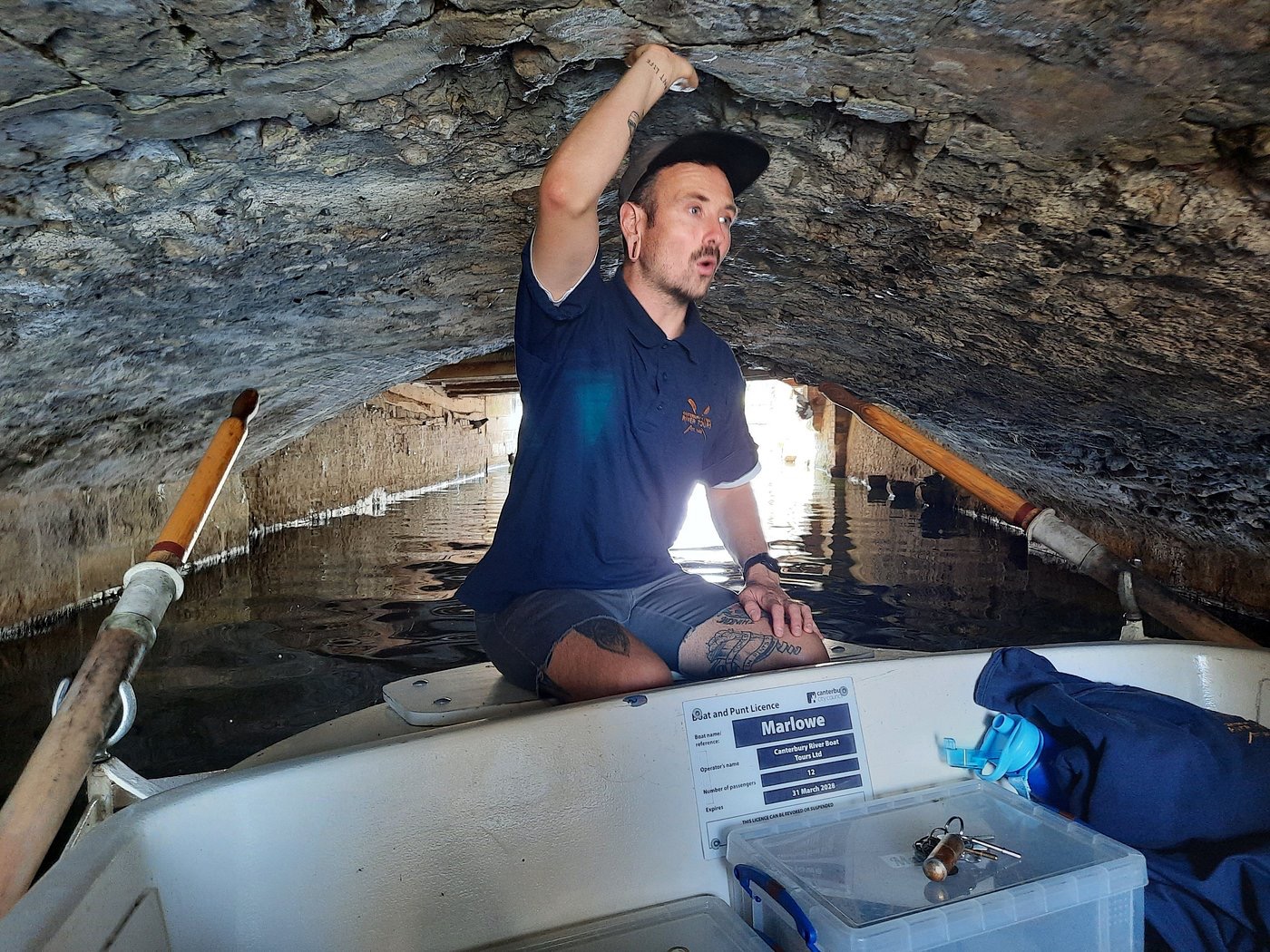

My job revolves around telling stories—real ones. Stories about the history of the city I live in, its twists and turns, and the eccentric characters who once walked the same streets I do now. Thomas Becket, Christopher Marlowe, Henry VIII… giants of their time, each one leaving a mark on the country as we know it. Religion, literature, relationships, politics—between them, they helped shape the entire landscape of modern Britain. In a strange way, I relate to them all. Not because I’m anything like a medieval martyr or a Renaissance genius (far from it), but because they remind me how powerful stories really are. How they outlive us. How they’re woven into everything we do.

People often tell me I’m a natural storyteller. It always makes me laugh, because if they only knew I’ve been making up stories my whole life. It was my first language long before I ever learned how to communicate with the world. Creation, imagination, invention—it's never left. And I don’t want it to. I don’t want to flatten that part of myself or think of it as a flaw. I just need to learn how to use it in a way that supports my life rather than pulling me away from it. I want to keep the storyteller but tame the escapist. Use the part of me that daydreams not as an escape hatch, but as a tool—something that enriches my world instead of replacing it.

Consider this another chapter in the book of Tadhg.

Post a comment